Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum

Superpowers are a fact of history. Before the Soviet Union and The United States, the British Empire was the world superpower. The Brits assumed “the white man’s burden” and carried back to England treasures to fill its museums with booty from many lands, most famously Greece, Egypt, and the Mideast. Skimming the cultures of less powerful people is not looked upon kindly as recent headlines illustrate. Yet, objects in British museums often fare far better than those left in their native country, especially in war torn areas of the globe. The National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad was one of the first casualties of the war.

Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum, an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through January 4, 2009, presents the gore and grandeur of one of the world’s earliest superpowers. At its height, around the 8th century BC, Ashurnasipal II proclaimed himself “great king, mighty king, king of the universe.” He wasn’t far wrong. His Neo-Assyrian empire, the largest the world had seen until then, included most of today’s Middle East, stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea, and encompassed all of present day Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, as well as large part of Israel, Egypt, Turkey, and Iran.

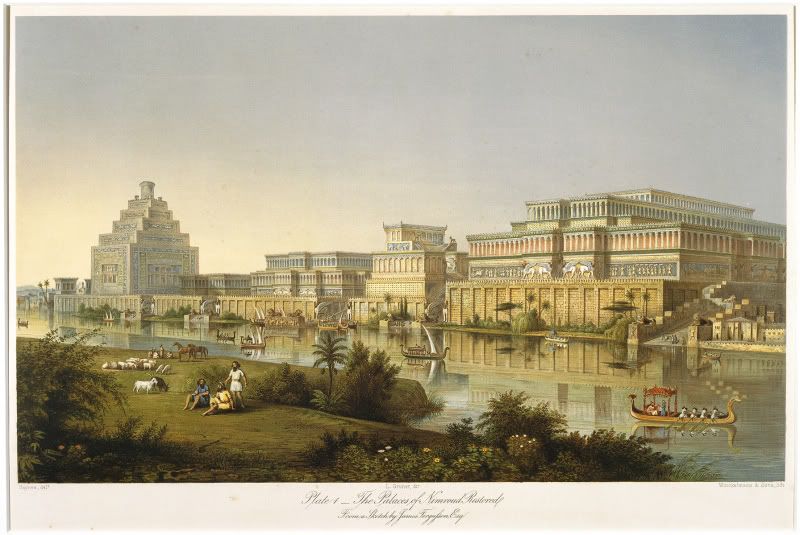

Still, not much was known about ancient Assyria until about two centuries ago when archaeologists rediscovered it. In the mid-19th century, French and British explorers built on the earlier work. Among them, the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard made notable discoveries. His interest was piqued by a large mount near Mosul. He thought it marked the site of ancient Nineveh. Instead, it was Nimrud, the ancient Assyrian city of Kalhu, called Calhu in the Bible. Later excavations included the work of such eminent archaeologists as Sir Max Mallowan, husband of mystery writer Agatha Christie. She set her Hercules Poirot novel Murder in Mesopotamia at an Assyrian dig.

The 250 objects in Art and Empire comprise several monumental wall reliefs that document important battles and victories. The King on Campaign (about 875-860 BC) shows a regal Ashurnashirpal II going into battle in Kurdistan. Escape across a river dramatizes an incident in 878 BC., when Ashurnashirpal II and his soldiers encountered enemies near the Euphrates River. The relief records Assyrian archers along the river bank shooting at the king’s men who are swimming to safety with the aid of inflated animal skins. Wall reliefs such as these adorned the magnificent interiors of the palaces. Carved on gypsum slabs with iron and copper tools, they paneled the bottom half of painted, mud-brick wall

The objects on display also include decorative ivory pieces, furniture fittings, sculptures, metal vessels, jewelry, and cuneiform clay tablets. These are rare pieces unearthed in palaces and temples dating from 9-7th centuries BC along the Tigris River in northern Iraq.They highlight the luxurious cosmopolitan lifestyle enjoyed by royalty.

Boston is the exclusive venue of Art and Empire, a collaboration of the British Museum and the MFA. The British Museum claims the finest collection of Assyrian art outside of Iraq.