Boston: African Art in Focus

For more than a century, African art has challenged the western imagination. How and why does an embroidered apron, for example, made in the 1970s by an unidentified, young South African woman, merit a place in a world-class museum? The answer may be found in “Object, Image, Collector: African and Oceanic Art in Focus,” the fascinating exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, through July 18. The exhibition traces the evolution of African artifacts from object to art.

“The impact of photography in promoting this shift has been neglected,” says Curator Christraud Geary. Photographs– the “image” referred to in the show title – are a key to understanding how utilitarian objects came to be regarded as art.

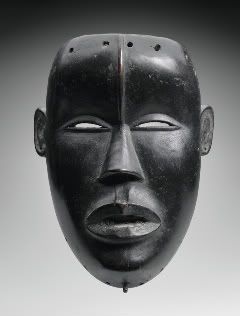

Mask (gle)

Unidentified artist, Mano peoples, Côte d'Ivoire/Liberia, early 20th century

Wood, iron

Private Collection

The exhibition comprises 50 chronologically arranged objects, drawn primarily from 20 private Boston-area collections. The most colorful display is a mask and hand-worked, embroidered and appliquéd costume made by Nigerian artist Lawrence Ajanaku of Ogiriga in 1974. Worn by a life-sized manikin, it represents an “ancient mother,” the senior character in a multimedia Edo spectacle.

Until the turn of the 20th century, ethnographic and history museums displayed the objects brought back from the European colonies in Africa and Oceania. In the early part of the 20^th century, however, /avant-garde/ artists seeking to escape the bonds of formalism found inspiration in the African masks and carved figures they saw at Parisian flea markets and the homes of friends. Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, along with other cubists, incorporated the new forms into their work.

Young woman’s apron (pepetu)

Unidentified artist, Ndebele peoples, South Africa, c. 1970

Glass beads, canvas, cotton thread

Suzanne Priebatsch and Nathalie Knight Collection

Clara Sipprell encountered African Art in Matisse’s studio. She photographed artist Max Weber with a small African figure similar to one in the MFA exhibition. Weber also featured the wooden sculpture in one of his paintings. He was among the first to introduce cubism to Americans.

Over time, paintings, publications, and photographs of the African objects by artists shifted public perception. The objects came to be perceived as art and the photographs did too. Many of the objects at the MFA are documented with photographs. Comparing the object with its image reveals how the camera may alter perception.

Male and female figures

Unidentified artist, Flores, Indonesia, early 20th century

Wood, shell, cloth

Dashow Collection

In 1914, to celebrate the 10^th anniversary of his 291 Gallery in New York, Alfred Stieglitz mounted an exhibition of African art from the collection of Parisian art dealer Paul Guillaume. He photographed the show, which was featured in Camera Work magazine.

Like Sipprell and Stieglitz, many artists used photographs to document African and Oceania art. Charles Sheeler received a commission to photograph New York attorney and patron of the arts John Guinn’s collection. Several Sheeler images are on view.

With African forms integrated into their artistic vocabulary, artists began looking for the next new thing. They found it in Oceania. In 1926 surrealist Man Ray photographed a male Indonesian ancestor figure for the catalog cover of a Paris gallery’s inaugural exhibition of Oceania.

The Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University mounted a display of “African and Oceanic Sculpture” in 1934, but the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition in New York the following year was a landmark. “African Negro Art” included 603 objects from 52 private collections and 16 museums. Walker Evans photographed the MOMA exhibition for a limited edition catalog. Curator James Johnson Sweeney stated in the catalog, “Today the art of Negro Africa has its place of respect among the esthetic traditions of the world.”

The MFA exhibition includes two work by American artist Romare Bearden. Mysteries,” a collage, and “The Train,” a photo-etching and color aquatint, incorporate African form..

In one of the most recent works, titled “Silex Male: Ritual,” Willie Cole presents a photograph of himself as a warrior from the Silex and Sunbeam tribes. The life-sized digital inkjet print from 2004 is a nude self-portrait of his back imprinted with scorch marks made by a household iron. The wall label explains that “the irons refer to the domestic work carried out by African-American women, the branding and scarification of slaves, and nineteenth century diagrams intended to show the brutal, inhumane conditions of slave ships.”

Currently, interest in African and Oceanic art focuses on utilitarian objects, metalwork, beadwork, pottery, and textiles, which explains why an apron by an anonymous South African woman is exhibited in a Boston museum.

All images provided by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.