An Open Letter to Jamaica Plain on The Whole Foods Effect

Dear Neighbors,

I have been listening deeply to the heated controversy incited by the news that Whole

Foods plans to open a new store in Hyde Square, the Latin Quarter of our neighborhood.

The lively debate of the past few weeks has inspired me to learn more, to research more,

and to better understand the extent to which the arrival of a Whole Foods Market should

be expected to contribute to gentrification in Jamaica Plain.

What I’ve learned is that for years journalists, real-estate agents, developers, and city

planning consultants around the country have been discussing a phenomenon called “The

Whole Foods Effect". "The Whole Foods Effect" refers to the impact of a Whole Foods

store on the value of surrounding real-estate and its magnet-like tendency to draw other

upscale stores. The Whole Foods Effect, I’ve learned, has been known to dramatically

accelerate the process of gentrification.

Perhaps the most well-known commenter on this subject is the CEO of Whole Foods

himself, John Mackey, who in a 2007 CNNmoney.com article said, "The joke is that we

could have made a lot more money just buying up real estate around our stores and

developing it than we could make selling groceries."i

While Mackey’s comment is both revealing and demonstrates a lack of concern about the

role his company plays in the gentrification of neighborhoods, he is hardly the only

person to point out this connection. Greg Badishkanian, an analyst with Citigroup who

tracks Whole Foods said in a 2006 NPR story, "When Whole Foods opens up a store in a

particular market, all of the real estate in the area gets a nice uplift. It could be a few

percent to 10, 15, 20 percent in terms of the real estate value."ii

Realtors, too, have been saying it for years. For example, in Southern California, real estate

agent Phillipe Rodrigue blogged in 2010, "one way to instantly increase property values is

to have a big, beautiful Whole Foods Market open up right in your neighborhood!"iii Much

like Rodrigue, a Chicago realtor named Brett Hutchins wanted to buy a condo near a new

Whole Foods in Sarasota, saying, 'I know what happens to real-estate values when Whole

Foods goes in.'"iv

Even a 2007 study in Portland, Oregon found that property values typically go up by

about 17.5% percent if you live nearby a Whole Foods.v

But out of all of the communities hit by the Whole Foods Effect, the Ward 2

neighborhood in Washington, D.C. is interestingly analogous to Boston’s Latin Quarter.

Ten years ago, at the turn of the century, D.C.’s Ward 2 went through a similar grocery

store turnover during a major shift in its population and income. The parallels portend

the risks that Hyde Square faces in welcoming a Whole Foods Market.

Neighborhoods in Transition

First of all, when the P Street Whole Foods opened in Ward 2, it replaced a more

affordable grocery store (across the street).vi Hyde Square’s affordable grocery store, Hi-

Lo (arguably the most affordable grocer in Jamaica Plain), is set to be replaced by Whole

Foods. So, in both communities, we see the transformation of an accessible grocery store

to an upscale one.

Secondly, both neighborhoods were inhabited primarily by people of color and then saw

these populations leave in large numbers during the ten years prior to catching the

attention of Whole Foods. In the decade prior to Whole Foods’ new P Street store in

Ward 2, the neighborhood’s African American population had declined by 23%.vii In

Hyde Square, the percentage of residents of Latin American descent has declined 26%

from 2000 to 2009.viii

Thirdly, as the racial makeup changed in each area, so did the income levels. The

Jamaica Plain neighborhood experienced a roughly 20% increase in income in the last ten

years, as did Ward 2 before the arrival of Whole Foods.ix

These similarities give us reason to look closely at what happened in Ward 2. There, the

arrival of Whole Foods was the “watershed event” in the neighborhood’s gentrification.x

Clearly, it didn’t start the process, but it did cause its acceleration.

Turning up the Heat

Even the Community Liaison for the P Street Whole Foods, Zachary Stein,

acknowledged it: “How do I see our store as part of the gentrification? The newer

residents wanted us to come, so we came and we catered to the newer residents…While

we didn’t cause it, it was already happening before we got here…it was well on it’s way

by the time we showed up, but I guess we sort of helped the process along.”xi

A group of 8th-graders took their mics out on the streets of Ward 2 and recorded people’s

views on the gentrifying impact of Whole Foods. Everyone seemed to acknowledge, as

one person put it, “[Whole Foods] didn’t start the gentrification, but it definitely helped

it.”xii Another said, “Anytime you see a Whole Foods, you know that’s gonna be a new

neighborhood. If a Whole Foods goes into a neighborhood, then you know that

neighborhood’s changing.”xiii It “made a statement that this was going to be an area for

wealthier shoppers.”xiv The P Street study concluded, “the appearance of Whole Foods

has dramatically increased the speed of gentrification in the area” – beyond the speed of

grassroots checks and balances.xv

Walking through Ward 2, you’ll now see new condos, new niche stores for the wealthy,

higher-end chain stores, older businesses that have had to adapt to survive, and new

businesses that replaced the ones that didn’t (or couldn’t) adapt. Property values have

escalated – the home of Wayne Dickson, who lobbied for the P Street Whole Foods, was

worth $230,000 in 1986 and is now assessed at $1.6 million (Dickson understood the

Whole Foods Effect before it even hit Ward 2.)xvi

The most poignant observation of the damage done by the Whole Foods Effect ironically

comes from Mr. Dickson, "We're losing a great number of our poorer neighbors and our

African American neighbors. Today there are only two remaining African American

families on this block. There have been people who have cashed out, who have done

very, very well -- but! They won't ever get back in."xvii

Some pre-existing residents may experience some specific benefits from some specific

aspects of The Whole Foods Effect. But overall, we see the faces of neighborhoods

changing.

As Fran Robertson, a long-time D.C. resident, put it, "A lot of the blacks are having to

move because they can't afford to stay here. These are people who have owned their own

homes but have had to leave because the taxes are going up. The affluent is coming in,

and the have-nots are moving out, and it's not right."xviii

Renters beholden to the private market are also displaced, not by “cashing out”, but by

being priced out. So the face of a neighborhood changes as the door is shut and locked

behind them, likely much quicker if you add The Whole Foods Effect.

Does Hyde Square want to live through the Whole Foods Effect much like Ward 2?

What does Hyde Square want to look like in 10 years?

The Jamaica Plain Effect

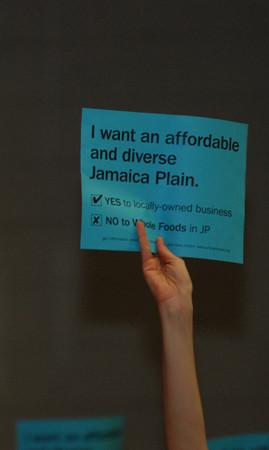

As the shadow of Whole Foods blankets Boston’s Latin Quarter, the corporation is seeing

something they’ve probably never seen before – a very large and well-organized group of

neighbors rising out of their armchairs, shutting their laptops, sweeping up their children

and gathering at public rallies and forums, demanding an affordable and diverse Jamaica

Plain without Whole Foods. They’ve launched a campaign called “Whose Foods?”,

collected hundreds of petition signatures, spoken out to the Neighborhood Council,

produced 4 videos, garnered the attention of major papers and blogs, gathered over 400

Facebook fans, written letters-to-editors, and created a bilingual web site that even nay-

sayers are calling “very slick” -- all in a handful of weeks.xix

I imagine that Whole Foods assumed Hyde Square would give ground in much the same

way as Ward 2. But Jamaica Plainers are unusual – not only have residents here

successfully kept out Dominos, Jack-in-the-Box, K-Mart, and a state highway, but there

are also some truly meaningful and rich ties between neighbors across race and class that

have quickly woven a network of resistance. This is the Jamaica Plain Effect – the

impact of a powerful, loving, grassroots community taking ownership of itself.

I stand with everyone who is opposed to a Whole Foods in Hyde Square. With hope and

faith, I ask my neighbors to join me.

Helen Matthews

Jamaica Plain resident since 2002

i CNNmoney.com, “The Man Who Brought Organics to Main Street”

ii NPR’s Next Generation Radio, “The Whole Foods Effect”

iii Trulia.com, “Tarzana Whole Foods Market Opens in 2010”

iv The Wall Street Journal, “If Whole Foods is Part of a Retail/Condo Complex, New

Apartments Sell Briskly”

v Johnson Reid, LLC “An Assessment of the Marginal Impact of Urban Amenities on

Residential Pricing”

vi Degan and Haber, “Washington, DC: The Impact of Whole Foods on 14th St. and

Greater Logan Circle Area”

vii Degan and Haber, ibid.

viii 2009 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau

ix OnBoard, LLC.

x Wikipedia, “Logan Circle, Washington, D.C.”

xi Public Radio Exchange, “Gentrification on Logan Circle”

xii Public Radio Exchange, ibid.

xiii Ibid.

xiv Degan and Haber, ibid.

xv Ibid.

xvi The Washington Post, “For D.C. couple, community activism launches lucrative real

estate careers”

xvii NPR’s Next Generation Radio, Ibid.

xviii The Washington Post, “Hungry for Whole Foods”

xix See http://www.whosefoods.org