Two Strong Exhibitions of Mexican Art at the MFA

Next year marks the centennial of the Mexican Revolution. Still, the country seems forever in flux. Two exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, present views of Mexico that not only differ from each other, but also from the pictures we’re used to seeing on travel brochures and in magazines.

Mexico has been called Edward Weston’s Paris. It is the only country the American photographer ever visited, and Viva Mexico! is about how he thoughtfully explored new techniques there in the 1920s and 1930s. By contrast, the companion exhibition, Vida Y Drama: Modern Mexican Printspresents bold, emotional images inspired by a long, tumultuous history.

Dictator Porfirio Diaz was a popular general when he first assumed power in Mexico. But by the early 1900s, he had established a militaristic government. A favored few amassed great wealth, mostly from foreign investments, but the majority of Mexicans suffered inflation, poor working conditions, and lack of opportunity. Some in the upper and middle classes, therefore, formed a coalition with the working class and peasants. They called for Diaz to step down. In 1908, he agreed to hold an election in November 1910. When it appeared that he would lose, however, he jailed his opponent and declared himself the winner. This was the match that ignited the Mexican Revolution. It ended El Presidente’s 30-year reign and ushered in a decade of social and political unrest.

Emliano Zapata commanded the Liberation Army of the South. Diego Rivera’s lithograph shows the Mexican folk hero dressed entirely in white and standing beside a white horse, the legendary white knight. Columns of peasants follow him. Zapata died in 1919. Rivera made the print in 1932, testimony to the respect and affection his countrymen reserve to this day for Zapata.

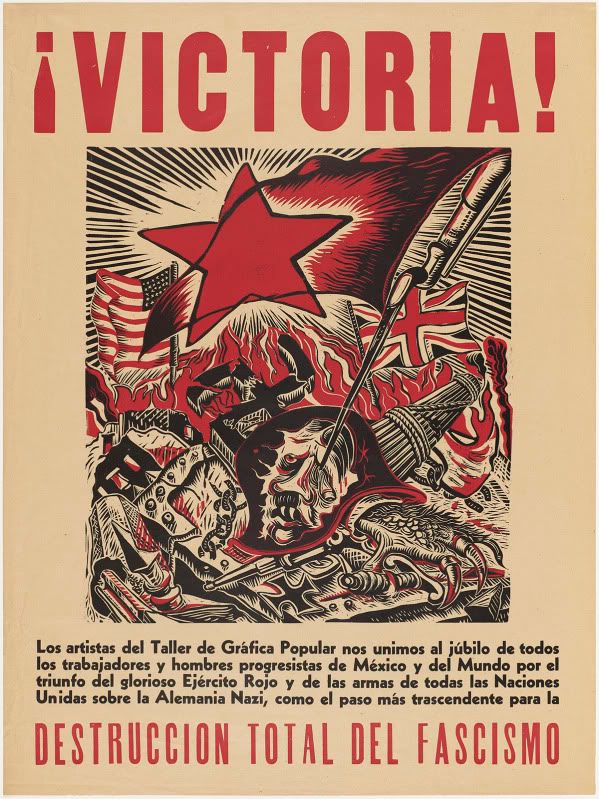

Titled simply “Zapata,” Rivera’s print is among the 27 artworks in Vida Y Drama, a socially conscious collection of art that erupted from visceral familiarity with poverty and recognition of injustices in Mexico and beyond to as far away as Adolph Hitler’s Germany. Leopoldo Méndez’s 1942 linocut “Deportation to Death” shows Jews being herded on the train that would take them to an extermination camp. Hitler had offered to help Mexico get back land it had lost to the United States, if Mexicans would send troops to fight with the army of the Third Reich. Mexico refused.

Mexico has a long history of printmaking. The first press arrived in 1539. Poor artists found prints inexpensive to make. Posters and political images by some of Mexico’s best known artists, including José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo, are among the most compelling in the exhibition.

By comparison with the explosive images in Vida y Drama, the photographs in Viva Mexico! Edward Weston and His Contemporaries are composed art, portraits, posed nudes, and still lifes from the 1920s and 1930s. Of the approximately 40 works in the exhibition, 30 by Weston, only one is by a Mexican-born photographer. Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s 1931 photograph, El sonador or “The Dreamer,” shows a man warmed by the sun and peacefully sleeping in the street.

Worker's Hands, 1927, Tina Modotti

Mexico attracted foreign artists because it was cheap, the climate warm, and the culture and landscape exotic. For Weston, who was born in the Midwest and living in California, it also offered an escape from domesticity. In 1923, he left behind a wife and three of his four children for the first of two extended trips to Mexico with his mistress, the Italian actress Tina Modotti, and his eldest son, Chandler.

On another trip, he took his son Brett to Mexico. Brett became a photographer and is represented in the exhibition. Modotti, who worked as Weston’s assistant and model, soon developed into a fine photographer in her own right. She made her sensitive image of worn hands resting on a shove and titled “Worker’s Hands” in 1927. The exhibition also features Paul Strand’s street scene “Dia de Fiesta, Mexico,” which resembles a still life, an arrangement of four men in sombreros leaning against a plain wall with the back of a woman in the lower left corner. Hungarian-born photographer Nickolas Muray is represented by a portrait of Frida Kahlo lent by a private collector.

This is the first exhibition of Edward Weston’s photographs from his sojourns in Mexico, which includes some of his earliest Modernist images. Among them are his nude photographs of Tina Modotti reclining on the roof of their studio, all of them titled “Tina on the Azotea.” He also photographed plants and still lifes. Weston’s technique with light and shadow and form abstracted his subjects into multi-dimensional shapes so that they appear like sculpture.

Both Viva Mexico and Vida y Drama will be on view at the MFA through November 2. During that time, the museum has scheduled tours of the exhibitions and special programs, including a tour in Spanish at 6:30 p.m. on the first Wednesday of the month. There’s also a Spanish audio guide and a Spanish language version of the MFA’s Map and Visitor Guide.

All photographs courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.