MBTA Suit Against MIT Charlie Card Hackers May Perpetuate Vulnerabilities

BOSTON - A suit brought against three MIT students last week by the MBTA prevented them from presenting their findings on Boston subway security vulnerabilities at the DEFCON conference in Las Vegas. Professional security researchers have expressed concerns that the gag order and the treatment of the students as criminals may dissuade researchers from identifying vulnerabilities in public systems for fear of litigation. As a result, vulnerable systems may remain unfixed and pose a risk to those who use them.

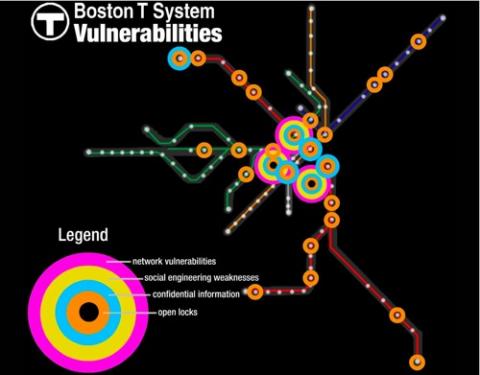

MIT students Zack Anderson, Alessandro Chiesa and R.J. Ryan were scheduled to present findings at DEFCON last Sunday on T system vulnerabilities including physical security, the RFID-based Charlie Card, the magnetic strip Charlie Ticket, and social engineering attacks. At several stations, the students identified unlocked or completely open security doors and turnstiles, turnstile control boxes, keys left unsecured, and unlocked, unattended surveillance rooms. Using hardware purchased online for about $50, the students were also able to reverse engineer both the paper Charlie Ticket and plastic Charlie Card, allowing them to add money values to the cards.

A federal judge in Boston found in favor of the MBTA, ordering the students not to provide "program, information, software code, or command that would assist another in any material way to circumvent or otherwise attack the security of the Fare Media System." Anderson said of the finding, "It was shocking. The Supreme Court has never upheld prior restraints on security researchers. It's protected speech." The MBTA originally requested that the students be prevented from discussing the fact that vulnerabilities even existed, but the judge denied this request. In an odd twist, the MBTA's lawyer has entered not only the students' DEFCON presentation into public record, but also a document they marked as "confidential" and never planned to publish because it contained key information necessary to hack the MagCard and RFID card. If the MBTA intended to keep the existence of these vulnerabilities a secret, they haven't done a very good job of it.

A group of eleven professional security researchers have written a letter to Judge George O'Toole, the judge overseeing the case, asking that the temporary restraining order be removed. They wrote that "Preventing researchers from discussing a technology's vulnerabilities does not make them go away - in fact, it may exacerbate them as more people and institutions use and come to rely upon the illusory protection. Yet the commercial purveyors of such technologies often do not want truthful discussions of their products' flaws, and will likely withhold the prior approval or deny researchers access for testing if the law supports that effort." They provide as examples of responsible hacking, cases in which security researchers discovered vulnerabilities in encryption used by banking systems, and one in which a plot to attack the White House's web server was revealed by reverse engineering. In each of these cases, security researchers provided evidence that helped eliminate vulnerabilities in systems the public uses.

Indeed, Anderson recognizes the role security researchers play in our increasingly technologically-mediated lives: "People who do this research have an obligation to society to advance technology, and it's unfortunate that instead, it's been perceived as an effort to disrupt it. [Hacking] is an intense dedication to learn how something works, to build something of value. In the true sense of the word, hacking is what has brought about the technological revolution. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak and Bill Gates would have all said they were hackers." Anderson stressed that his group never published any code, and that the software they were going to release was benign data visualization and pattern finding tools non-specific to the T system's Charlie Card or Charlie Ticket. "The most important thing is we didn't want anyone to circumvent the MBTA system. We wanted to fix the system."

In spite of all the attention his team's efforts have attracted this week, Anderson won't allow his work to be affected. "I don't think it's changed my perception of hacking, but it makes me want to be a lot more careful about disclosure." Fortunately for him and other researchers, the Electronic Frontier Foundation's new Coder's Rights Project, which launched just days before the suit was filed, seeks to protect their work. According to EFF Media Coordinator, Rebecca Jeschke, "If they are unable to do this research, all our systems will be weaker. On our site, we have a reverse engineering and a security FAQ on how to report a security vulnerability. Programmers should look at that."

When asked what the MBTA was doing to address the security vulnerabilities that are now accessible via public records, Lydia M. Rivera, an employee at the MBTA Public Affairs Department said, "We're in the preliminary stages of reviewing the findings. Further action will be taken if necessary." However, when asked about physical security vulnerabilities such as open turnstiles and the ease with which riders can enter green line cars without paying a fare, Rivera denied such problems existed. "Green line employees stand at the doors to make sure people have their proper fare. We do it at outlying stations, surface level stations. The MBTA spent a lot of money on fare gates, and they work." When asked about how much money the MBTA may be losing to fare evasion, and whether a proposed fare hike would be unnecessary if security was implemented properly, Rivera refused to comment. She added, "The MBTA continues to evaluate security and to enhance and improve how we collect our fares."

One last laugh (if you're not still laughing from that last quote): check this video for a teaser of Anderson's "warcart." According to the MIT group's DEFCON presentation, they attracted some attention while warcarting their way to MBTA's offices. Anderson laughed, saying, "We were stopped, but it wasn't any problem. The police saw our MIT T-shirt and said 'oh, MIT.' We didn't want it to turn into any serious terrorist scare." Right, Boston's had enough of those.

Comments

An interesting article. Thanks for the insight.

Fareless in Boston is also

Sheepless in Seattle...

It's interesting how our understanding of free speech has evolved to include software code. The EFF is doing a great job protecting us geeks, and the rest of the world who rely on us.